Charles Darwin: Evolution of the Origin of Species, Part I

"In June 1842 I first allowed myself the satisfaction of writing a very brief abstract of my theory in pencil in 35 pages; and this was enlarged during the summer of 1844 into one of 230 pages, which I had fairly copied out and still possess." —Charles Darwin, Autobiographies (1876)

Evolution of an Outline

Anyone who has sat on an idea, unable to quite release it into the world until it were just a little bit better, might find it easier to relate to Charles Darwin. It took him twenty years to publish his theory of natural selection, and even then, he was only propelled to do so because someone threatened to present the same idea before Darwin could lay claim to it.

Over those twenty years, Darwin recorded his notes on the theory of evolution in notebooks, sketches, essays, and multiple drafts. In this article, we take a look at the first sketch Darwin wrote out in 1842 in which he outlines his views on natural selection. Here we analyze the "thinking marks" of revision as Darwin struggled to put down to paper the argument that had been brewing in his mind and notes since his visit to the Galapagos Islands in 1835-1836.

The "1842 Pencil Sketch," as the manuscript is referred to, is Darwin's first attempt at articulating his theory with some kind of order and sustained prose.

Natural Rejection

"Formerly I used to think about my sentences before writing them down; but for several years I have found that it saves time to scribble in a vile hand whole pages as quickly as I possibly can, contracting half the words; and then correct deliberately. Sentences thus scribbled down are often better ones than I could have written deliberately." —Charles Darwin, Autobiographies (1876)

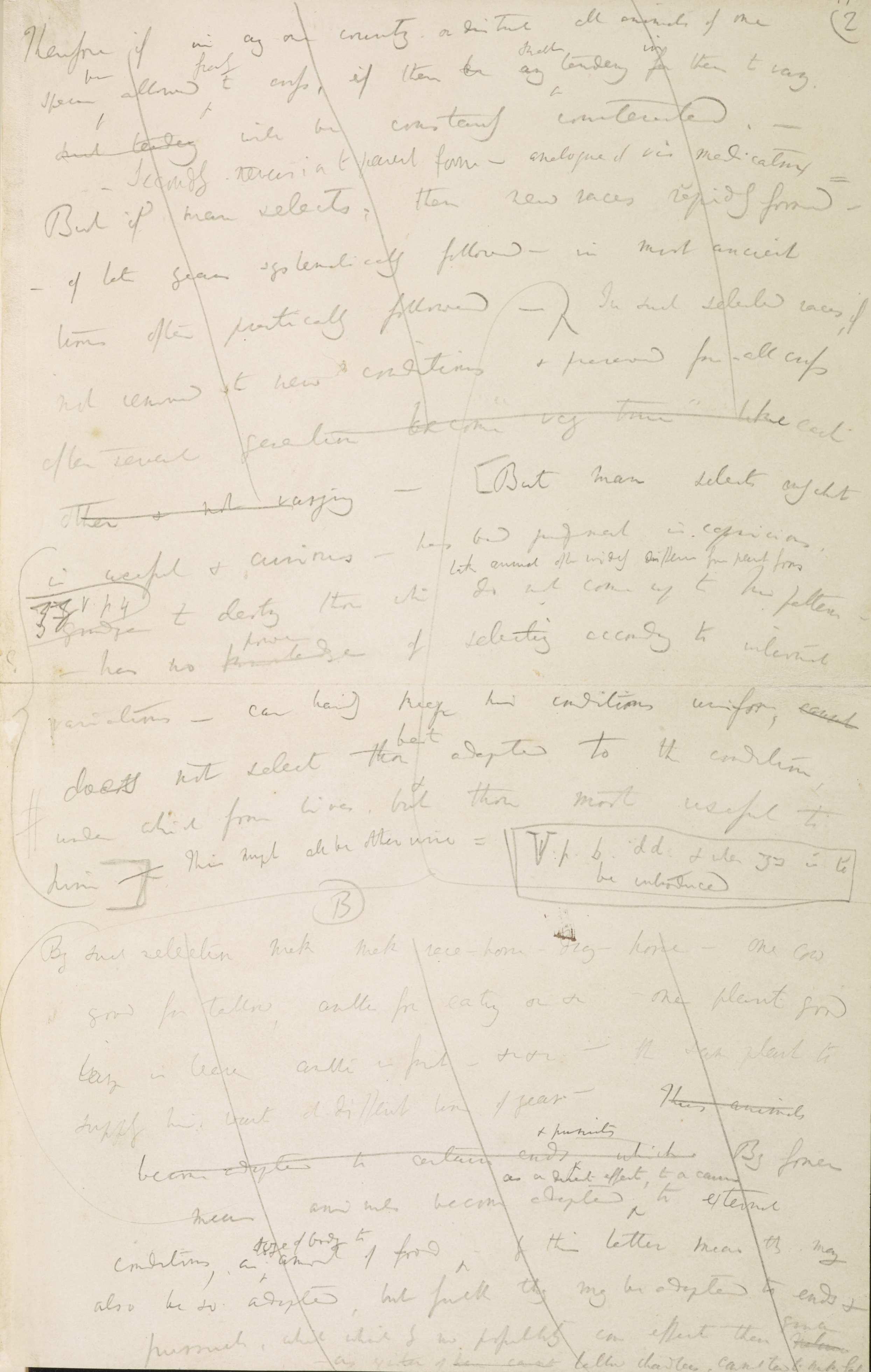

The thirty-five pages from the 1842 Pencil Sketch demonstrate the progress made through a tenacity to push through the starts and stops of writing. The two pages below mark Darwin's first attempts at beginning the sketch.

As one reads the various markings that fill the page, one can almost trace Darwin's movements. He begins with a crisp, clear sheet of cream colored paper and eventually fills it with text that doesn't necessarily flow from the other. The challenge at this point is not the creation of thoughts, but the organization of them, the articulation of coherence. He is finding a rhythm. The right starting point, it seems, will unleash a steady pace of writing (perhaps also of thinking). He squeezes in some thoughts at the bottom of the page before turning the paper sideways to add a few marginal notes. One of these notes, "Every organism, as far as our experience" seems to click. He turns the page over and starts the phrase again, but now with room to continue. "Every organism, as far as our experience goes when bred for some generations..." He seems to have found his stride and writes more freely.

The previous work is not in vain, however. Having found a footing, he decides to add sections from the abandoned first page to the "true" first page. AA) BB) PP) point to where the respective texts should be added. The near-vertical cross outs are believed to be Darwin’s way of signifying that he had incorporated the fragments of texts as he wrote and in subsequent rewritings.

Use It or Lose It

The following two pages capture a significant moment in Darwin's work. The image on the left (Ms p <5>) contains text that was crossed out before turning the page over to begin again. One nugget of these efforts was the first use of the term natural selection. In Ms p <5>, Darwin uses the term "means of selection" and then inserts a plus sign and the word "natural" to create the phrase "natural means of selection." It isn't until he turns the paper over that he coins the final and now very famous phrase "natural selection."

Generation 2.0

When looked at closely, the "thinking marks" shown here reveal Darwin shifting ideas around as though they were building blocks. An editorial carrot in the first paragraph sweeps down to collect section B written below. A boxed note is written on the right-hand side that states "V. p. 6. dd & where zz is to be introduced."

Furthermore, the editors at the Darwin Manuscript Project comment that some notes located on this page are evidence of Darwin referring to the 1842 Pencil Sketch while working on his 1844 Essay. The editors state:

The possibility that 1844 pencil notes may form a layer of the material in the 1842 Sketch suggests that in composing the 1844 Essay CD [Charles Darwin] may, at least in part, have first marked out, then pieced together, and then reworked fragments drawn from diverse parts of the 1842 Sketch.

The 1842 Pencil Sketch illustrates the work of revising that goes into honing an idea. The early sketch marks the start of an idea emerging from mind to paper, from the introspected to the articulated. His iterations reveal an evolution where scratch-outs, additions, and scribbles eventually work towards an idea that manages to survive on its own in the wild.

Special thanks to the American Museum of Natural History's Darwin Manuscripts Project and to Professor David Kohn, Director of the Darwin Manuscripts Project.

© Transcriptions, textual notes, interpretative commentary, bibliographic and biographical material reproduced by permission of the American Museum of Natural History. All rights reserved.

Additional Resources

To see the entire 1842 Pencil Sketch, visit the American Museum of Natural History's Darwin Manuscripts Project. The editors provide a transcript of each page with commentary (see the editors' notes on the symbols of the transcriptions).

For notes on the sketch and how it contributed to the 1844 Essay and final Origins, see Frances Darwin's introduction published in 1909 after the papers were discovered in a closet under the stairs of the old family home.

To read more about how Darwin’s idea benefitted from a bit of competition, check out the story of Alfred Russel Wallace, the man who sent Darwin his thoughts on natural selection from halfway around the world before Darwin had yet to publish his own thoughts on the same topic.

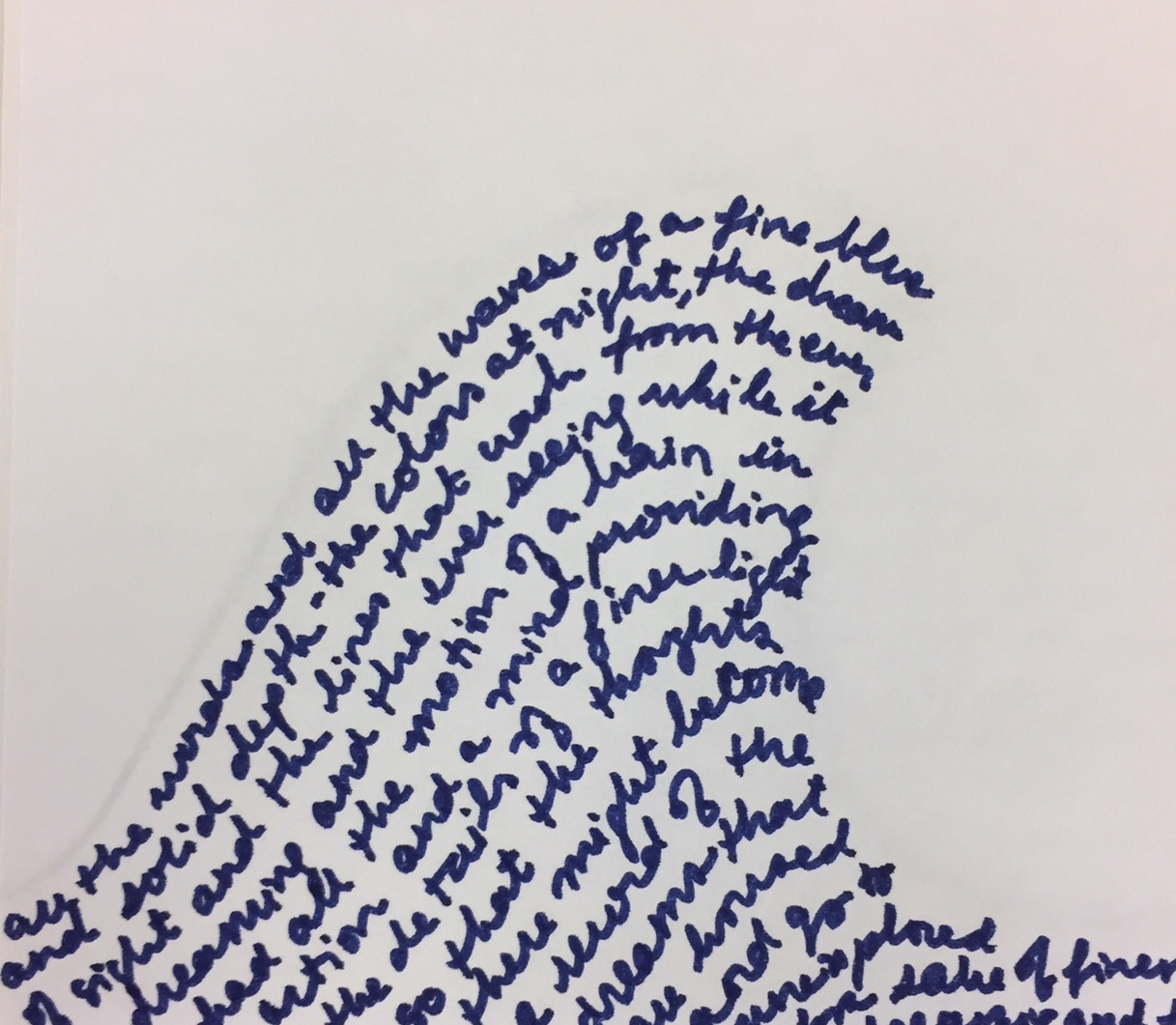

*Frontispiece

"Contents and Omissions," from Charles Darwin's 1842 Pencil Sketch. Reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library and William Huxley Darwin. Higher resolution images available from Cambridge Digital Library

Transcription and apparatus © American Museum of Natural History