Ernest Shackleton: Endurance, Part I

The Epic Tale of a Failed Feat

There is no hiding the fact that the 1914 expedition to cross Antarctica was a failure: not one of the crewmen set foot on the icy continent. The expedition, nonetheless, is an epic tale that outlives the decades. Despite the huge detour from the goal that all had held in sight, the journey and the expedition's leader, Sir Ernest Shackleton, remain a fixture among stories of perseverance, leadership, and survival.

It is said of Shackleton that what fueled his ambition was the prospect of glory. The 1914 journey was already his third attempt at hard-earned recognition as an explorer of "firsts." In 1902, after covering 960 miles towards the South Pole with the Scott Expedition, the group of three men were forced to turn around and return to home base. Shackleton, suffering from scurvy, was sent back home while the others continued their exploration of Antarctica. His 1907 attempt was foiled roughly 100 miles away from the Pole; four years later, Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his crew of four claimed the titled of being the first to reach the South Pole. Still determined, Shackleton revised his goal and set about to become the first to cross the entire continent.

Any mission to the perilous and unforgiving Antarctic requires a clarity of goals and meticulous preparation. Steadfast determination must also be paired with an adaptability to the twists and turns of an arduous journey. Constant assessment of one's progress—even if it means a reconsideration of what can be accomplished—may be the deciding factor of the final outcome. The journeys of those who travel through arduous terrains share a commonality in how we work our way towards realizing our goals and ideas. One step at a time, we may traipse, glide, or stagger our way through the preparation and toil that brings us closer towards our destination.

The Landscape of the Mind

While the story of Shackleton's 1914 expedition started out with the goal of crossing the Antarctic, it is much more a story that involved abandoning one destination in favor of reaching another: surviving the long journey back home. An even deeper look reveals that the trek home consisted of multiple, seemingly impossible journeys. Each journey was a trial that tested their skill, endurance, and spirit in the fight to continue.

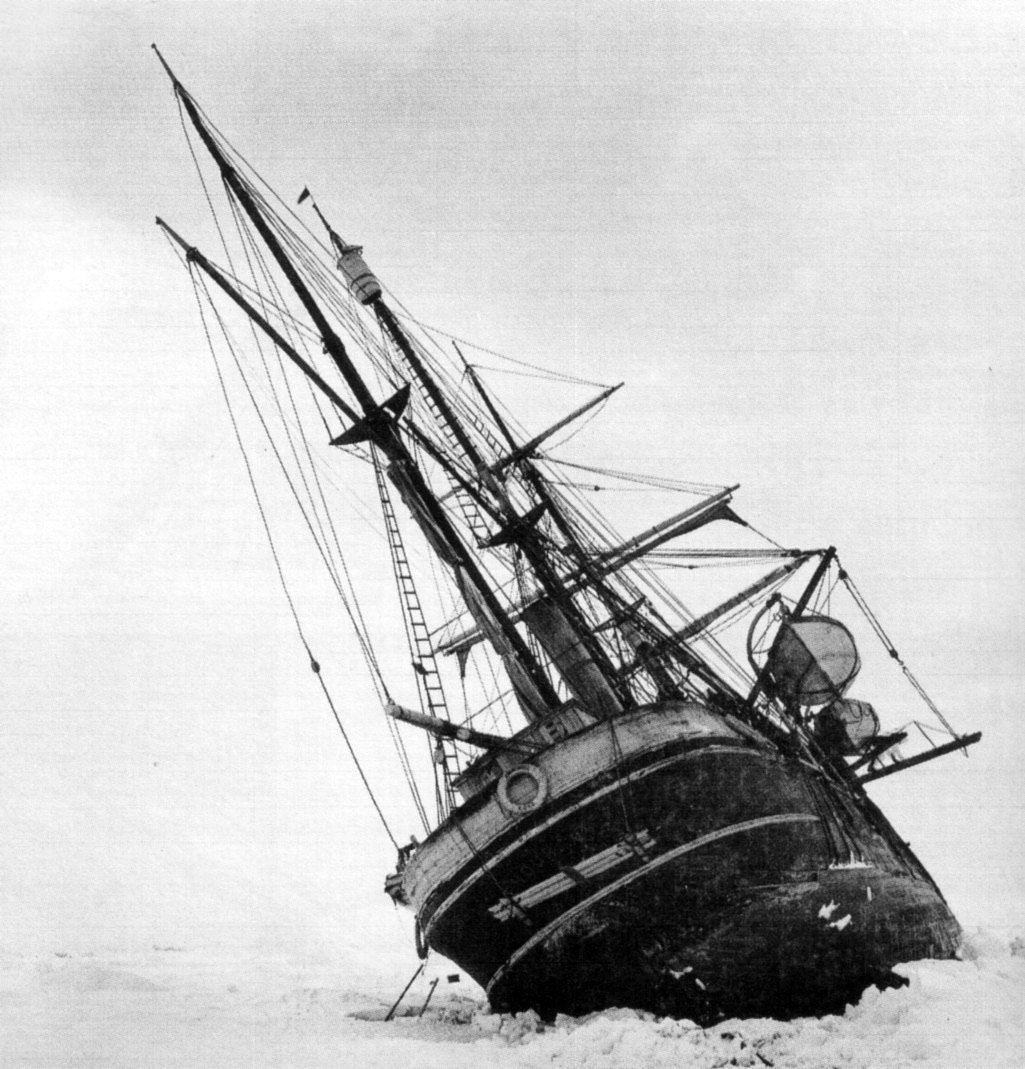

At times, the difficulty of our journey can alter the landscape of our mind as our thoughts take on sharper edges. The men not only had to struggle against nature's obstacles, they also had to face their own fears. When the men's ship, the Endurance, was locked between ice floes, it was only a matter of time before the ship would be crushed by the pressure of the surrounding ice. After months of drifting in the ice pack in the shelter of the ship, the men left the shelter of their ship to camp nearby. On November 21, 1915, the Endurance was squeezed to the point of sinking. In South, Shackleton's account of the expedition, he shares an entry from his diary:

'After long months of ceaseless anxiety and strain," I wrote," after times when hope beat high and time when the outlook was black indeed, the end of the Endurance has come. But though we have been compelled to abandon the ship, which is crushed beyond all hope of ever being righted, we are alive and well, and we have stores and equipment for the task that lies before us. The task is to reach land with all the members of the Expedition. It is hard to write what I feel. To a sailor his ship is more than a floating home, and in the Endurance I had centered ambitions, hopes and desires.'

In the video below from the American Natural History Museum, we see that the men had not let the ship go without a fight of their own. While the ice built up around her hull, each day the men would chip away at the ice in an attempt to unlock the ship from its grasp. The work helped to lessen the amounting pressure upon the ship, but perhaps more importantly, it gave the men a purpose and the sense that they were doing all that could be done. This spirit carried them through to the next arduous journey.

View the American Natural History Museum's video by Sarah Galloway, "Break-up of the Endurance." The film shares footage from Frank Hurley's archives (licensed from the British Film Institute). © 1999 AMNH

As the men floated on the ice floes—pushed northward by the wind—they found themselves not so far from where they had started. Shackleton explains, "Thus, after a year's incessant battle with the ice, we had returned to almost identically the same latitude which we had left with such high hopes a year before." On November 21, 1915, after nearly a month after having set up camp about a mile away from the ship, the Endurance was squeezed to the point of sinking. In South, Shackleton quotes from one of the crewmen's diaries:

‘This evening, as we were lying in our tents, we heard the Boss call out: “She’s going, boys!” And, sure enough, there was our poor ship a mile and a half away, struggling in her death agony. She went down bows first, her stern raised in the air. She then gave one quick dive and the ice closed over her for ever….Without her our destitution seemed more emphasised, our desolation more complete. The loss of the ship sent a slight wave of depression over the camp….I doubt if there was one amongst us who did not feel some personal emotion when Sir Ernest, standing on the top of the look-out, said somewhat sadly and quietly: “She’s gone, boys.” It must, however, be said that we did not give way to depression for long.’

By mid-December, Shackleton was highly aware of the melting ice and the danger this posed for the crew's camp. In an effort to lessen the distance to land, the crew prepared for one of their first marches. With their pack of dogs, three lifeboats, and supplies in tow, they set out for the first leg of their journey without the Endurance. Shackleton recounts the reality they faced after seven days of intense struggle and only seven and a half miles to show for it:

We had been on the march for seven days; rations were short and the men were weak. They were worn out with the hard pulling over soft surfaces, and our stock of sledging food was very small. We had marched seven and a half miles in a direct line, and at this rate it would have taken us over 300 days to reach land away to the west. as we only had food for forty-two days there was no alternative but to camp once more on the floe and to possess our souls in patience until conditions appeared more favourable for a renewal of the attempt to escape.

And so it was that the men would spend the next several months in their new home at Patience Camp. After nearly a year of treacherous obstacles and revised plans, the men were nonetheless determined to reach home. They would spend the next half year fighting against the elements and maintaining their will to survive. To learn more about the second half of the men's journey, read Part II of Ernest Shackleton: Endurance.

Additional Resources

While the expedition itself is a remarkable feat, another incredible aspect of the journey is the amount of documentation the men were able to maintain and preserve. Official photographer on the crew, James Francis (Frank) Hurley, managed to preserve roughly 150 images. Upon abandoning the ship, Shackleton forced Hurley to break 400 negative glass plates due to their heavy weight for the long treks ahead of them. Together they selected 120 glass negatives of the best images. Hurley shot a remaining 38 photographs by using a hand-held camera (as it has also been necessary to leave behind a number of larger cameras). To see thumbnail images from the Hurley collection, visit the Royal Geographical Society.

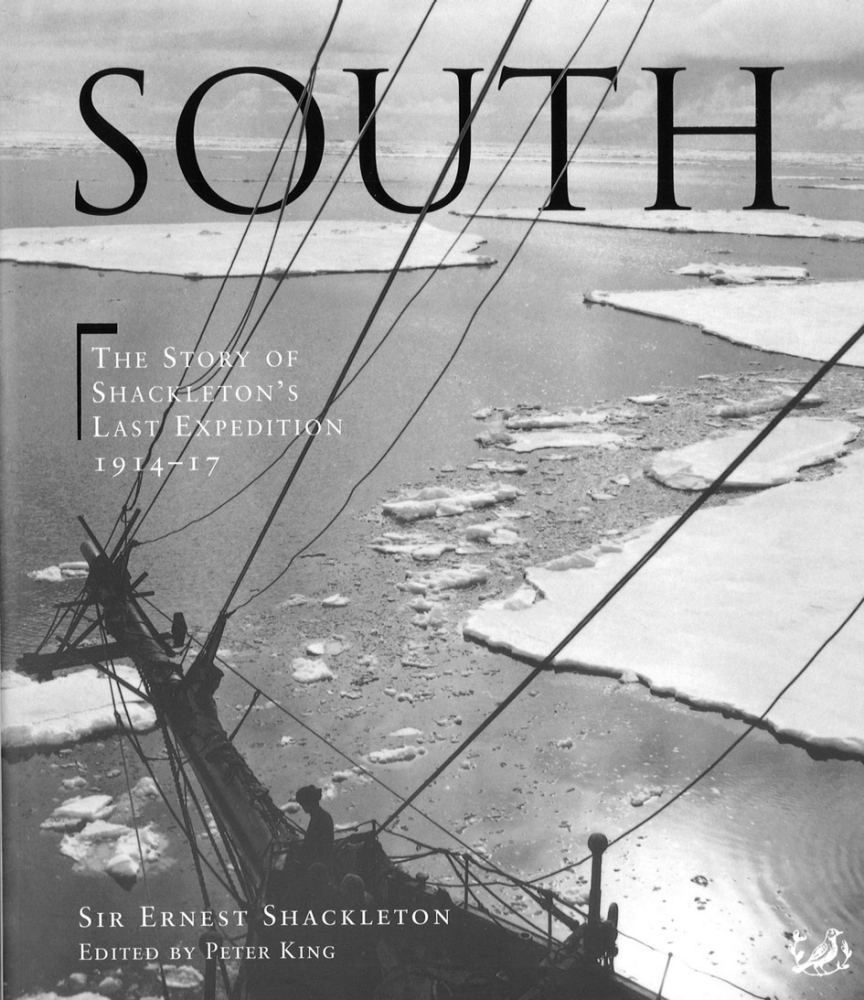

Three years after Shackleton's return from Antarctica (and upon his return from fighting in World War I), Shackleton published his account of the expedition in 1919. Today, various editions exist—some include editor's notes in the margins and photographs that illustrate the written accounts by Shackleton, and some are abbreviated versions of Shackleton's original. The beautifully annotated version by Peter King includes photographs from various archives, including those from the Royal Geographical Society and the Scott Polar Research Institute.

The film Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance (2002) by NOVA is told with captivating footage from Hurley's films and photographs, as well as with modern-day footage of the same route. The film also includes stories from the children and grandchildren of many crew members on the expedition. NOVA's accompanying website, Shackleton's Expedition, provides a wealth of resources.

Alfred Lansing's Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage provides a riveting account of the journey. First published in 1959, the book renewed interest in Shackleton's story. There are many (many!) other accounts that highlight the journey.

*Frontispiece

Hurley, F. (1915) "The stern of the 'Endurance' keeling over." Royal Geographical Society Image no. S0000842