Wright Brothers: A Flying Idea, Part I

"The role of the artist, like that of the scholar, consists of seizing current truths often repeated to him, but which will take on new meaning for him and which he will make his own when he has grasped their deepest significance. If aviators had to explain to us the research which led to their leaving earth and rising in the air, they would merely confirm very elementary principles of physics neglected by less successful inventors." —Henri Matisse, "Notes of a Painter"

Though attempts at flight had been made for centuries before the Wright Brothers claimed the honor of achieving this feat, the key had been available to all who had ever gazed upon a bird in flight. But as anyone who has enjoyed watching a bird fly across the sky will know, the secrets of such insight are not immediately bestowed; ideas tend to require greater nurturing than observation alone. Rather, it is the meaning drawn from observation that makes such moments significant.

Through the documents made available by the Wright Brothers, we can trace a direct line from bird to plane. Their reading logs, notebooks, photographs, and letters provide a record of how they laboriously pieced together the necessary parts for understanding.

The Wright Brothers approached their interest in flight with a material view of how understanding is acquired. Like the mechanics they were, they seemed to think they could build their understanding. Theirs was a method that sought facts and ideas as one might seek the relevant parts needed to manufacture a new object. They took apart the apparatuses of understanding pieced together in previous attempts at flight. The successes and failures of other men's attempts served as valuable sources of information. They pushed aside the bulkier, unnecessary elements until they formed a prototype that would get them as far as they could go until a new one was needed to accommodate their "improved" understanding.

Reading and Observing: A Quest for Information

Their interest in flight began in 1896 when Wilbur Wright learned that the German engineer and flight experimenter Otto Lilienthal had died after a crash in his glider. Wilbur's interest in flight piqued, and with Orville suffering in bed from typhoid fever, Wilbur read aloud much of Lilienthal's work. Influenced by Lilienthal's conjecture that the secret of aviation might be found by studying birds in flight, Wilbur began reading whatever was available on the topic of bird flight. He began with his father's home library and later moved onto the local library. Here he read books such as Etienne-Jules Marey's Animal Mechanism, and J. Bell Pettigrew's Animal Locomotion; or Walking, Swimming, and Flying, with a Dissertation on Aeronautics.

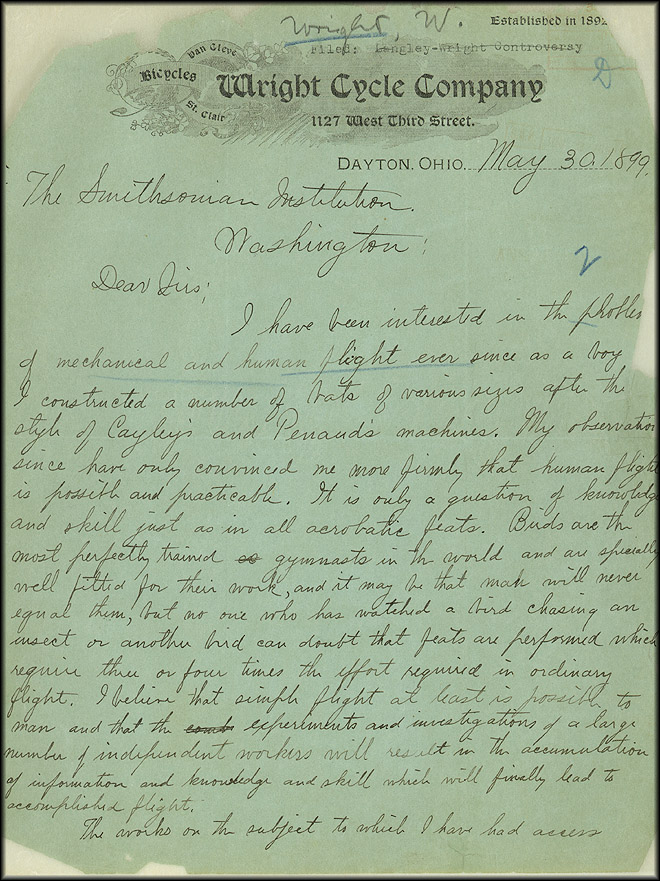

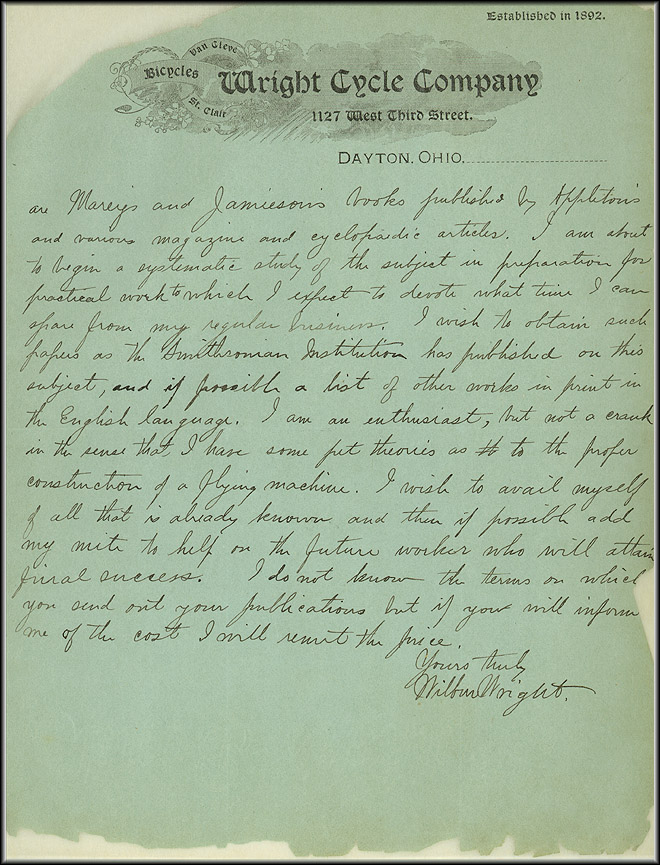

By 1899, Wilbur outgrew the resources available to him and began to seek additional material that could aid him in his research. On May 30, 1899, Wilbur wrote his first letter to the Smithsonian Institution asking for reading materials and recommendations. He opens the letter by stating his interest in "the problem of mechanical and human flight." He writes that it is "only a question of knowledge and skill just as in all acrobatic feats." It is worth noting that in this early stage, Wilbur hoped to merely contribute to the greater understanding of flight (and not necessarily to become the first to fly): "I wish to avail myself of all that is already known and then if possible add my mite [sic] to help on the future workers who will attain final success."

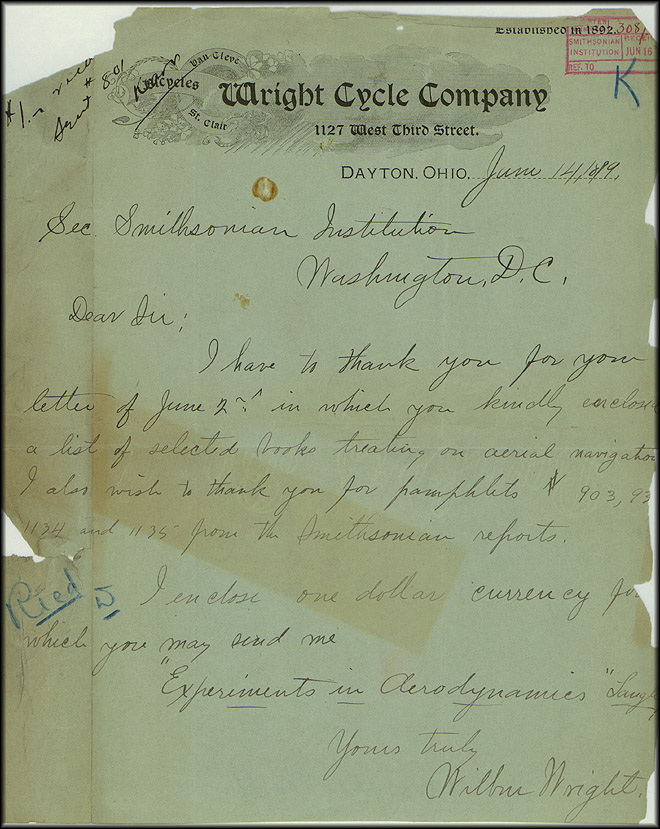

The following images are courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives (where a transcript accompanies the images). Also included below is Wilbur's thank you note written on June 14, 1899 after receiving pamphlets published by the Smithsonian Institution and a list of reading recommendations provided by the assistant secretary of the Smithsonian, Richard Rathbun.

First Steps: Moving into Action

Wilbur and Orville's research provided them with enough breadth of understanding to begin to piece together the necessary parts towards their goal. The first step in this process, as later articulated by Wilbur in 1908 in his first speech on the topic, was to define the problem space:

The difficulties which obstruct the pathway to success in flying-machine construction are of three general classes: (1) Those which relate to the construction of the sustaining wings; (2) those which relate to the generation and application of the power required to drive the machine through the air; (3) those relating to the balancing and steering of the machine after it is actually in flight.

Of these three difficulties, the brothers recognized that the key to discovery lay in the final class, maintaining equilibrium in air.

What is interesting about reading Wilbur's 1908 speech is how the brothers worked with the long view in mind. The brothers understood that they were searching for the foundational principle underlying flight. In the case of motors and wings, the foundational principles had already been discovered. In relation to flight, these were mechanical obstacles. The secret of maintaining equilibrium in air, however, was essential. "When this one feature has been worked out," Wilbur remarked in the speech, "the age of flying machines will have arrived, for all other difficulties are of minor importance."

For the brothers, identifying the problem in such a way was crucial to determining next steps. We can see a mechanic's mindset at work. The mechanic puzzles over the specific source of trouble before, say, taking apart everything under the hood of a car. Their research confirmed for them how they should apply their future efforts: study the birds and start building.

In another example of classifying their options, the brothers presented themselves with two related to practice. They could either think their way to flight, or they could try by application. As Wilbur framed it in his speech, the decision was clear:

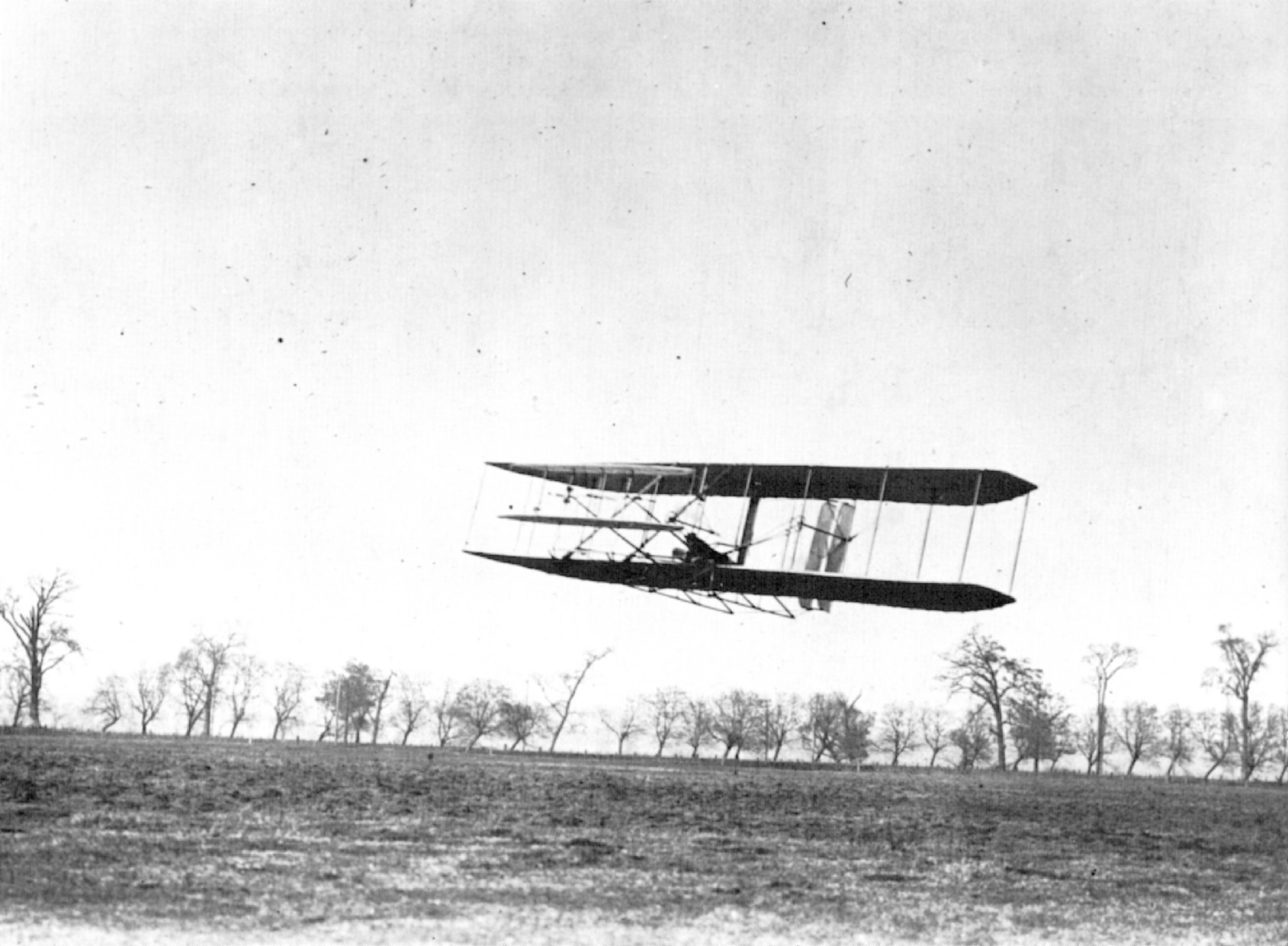

The bird has learned this art of equilibrium, and learned it so thoroughly that its skill is not apparent to our sight. We only learn to appreciate it when we try to imitate it. Now, there are two ways of learning to ride a fractious horse: One is to get on him and learn by actual practice how each motion and trick may be best met; the other is to sit on a fence and watch the beast a while, and then retire to the house and at leisure figure out the best way of overcoming his jumps and kicks. The latter system is the safest, but the former, on the whole, turns out the larger proportion of good riders. It is very much the same in learning to ride a flying machine; if you are looking for perfect safety, you will do well to sit on a fence and watch the birds; but if you really wish to learn, you must mount a machine and become acquainted with its tricks by actual trial.

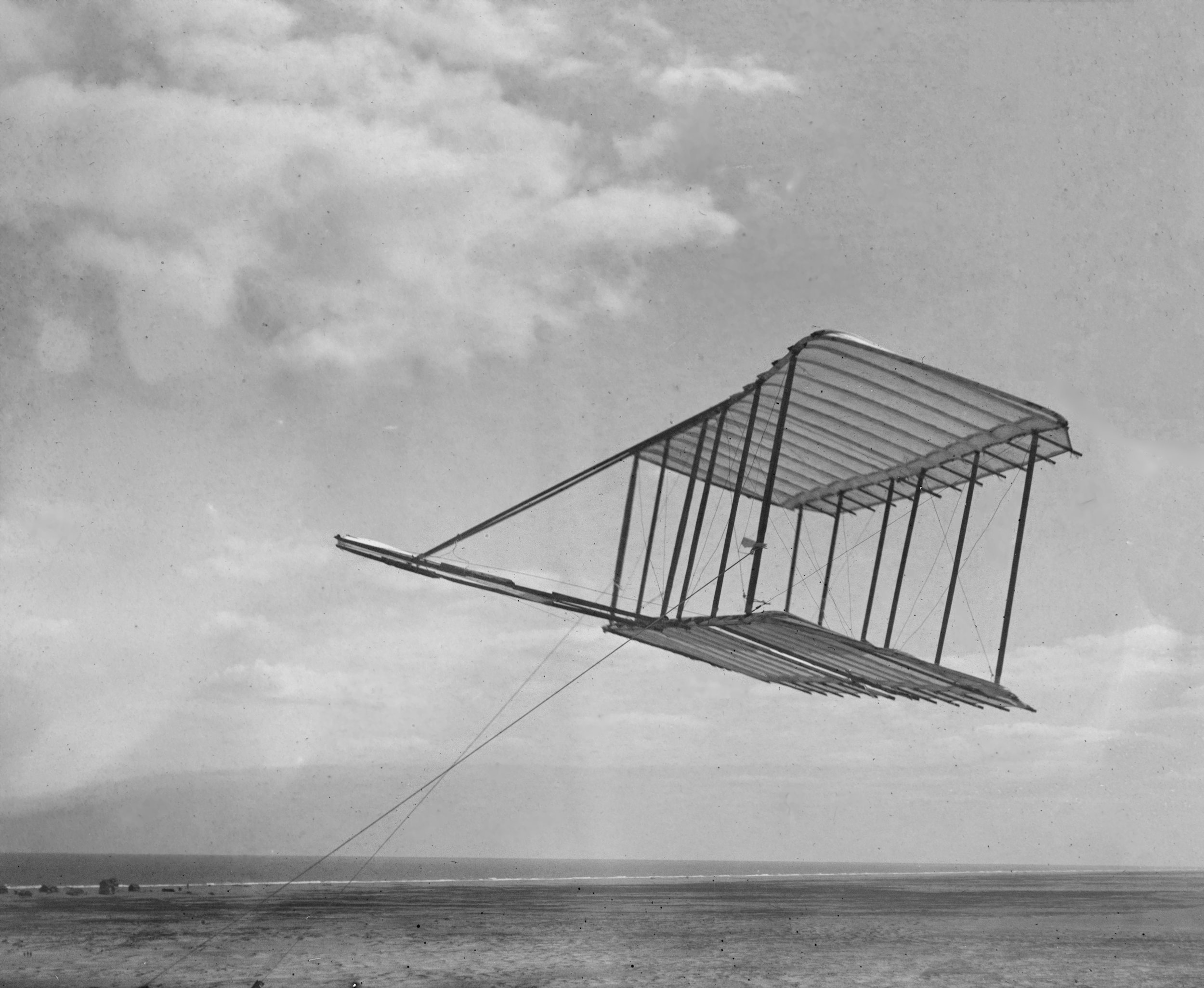

By the late summer of 1899, the brothers had built their first kite with a wingspan of five feet modeled after Octave Chanute's biplane design (one set of wings over another set). By 1900, the brothers were ready to put their ideas to action and began to seek the ideal location for experimentation. On May 13, 1900, Wilbur wrote his first letter to Octave Chanute asking for his recommendation for an ideal place to test their glider. In the letter, he shares his goal and plan for gaining enough height in the air to be able to practice "by the hour instead of by the second." In explaining his plans, he writes, "my object is to learn to what extent similar plans have been tested and found to be failures, and also to obtain such suggestions as your great knowledge and experience might enable you to give me."

Ten years of correspondence between the Wright Brothers and Octave Chanute are held in the Octave Chanute Papers at the Library of Congress. Below you can read Wilbur's first letter to Chanute. A complete transcript of Wilbur's letter and Chanute's response can be found at the links provided.

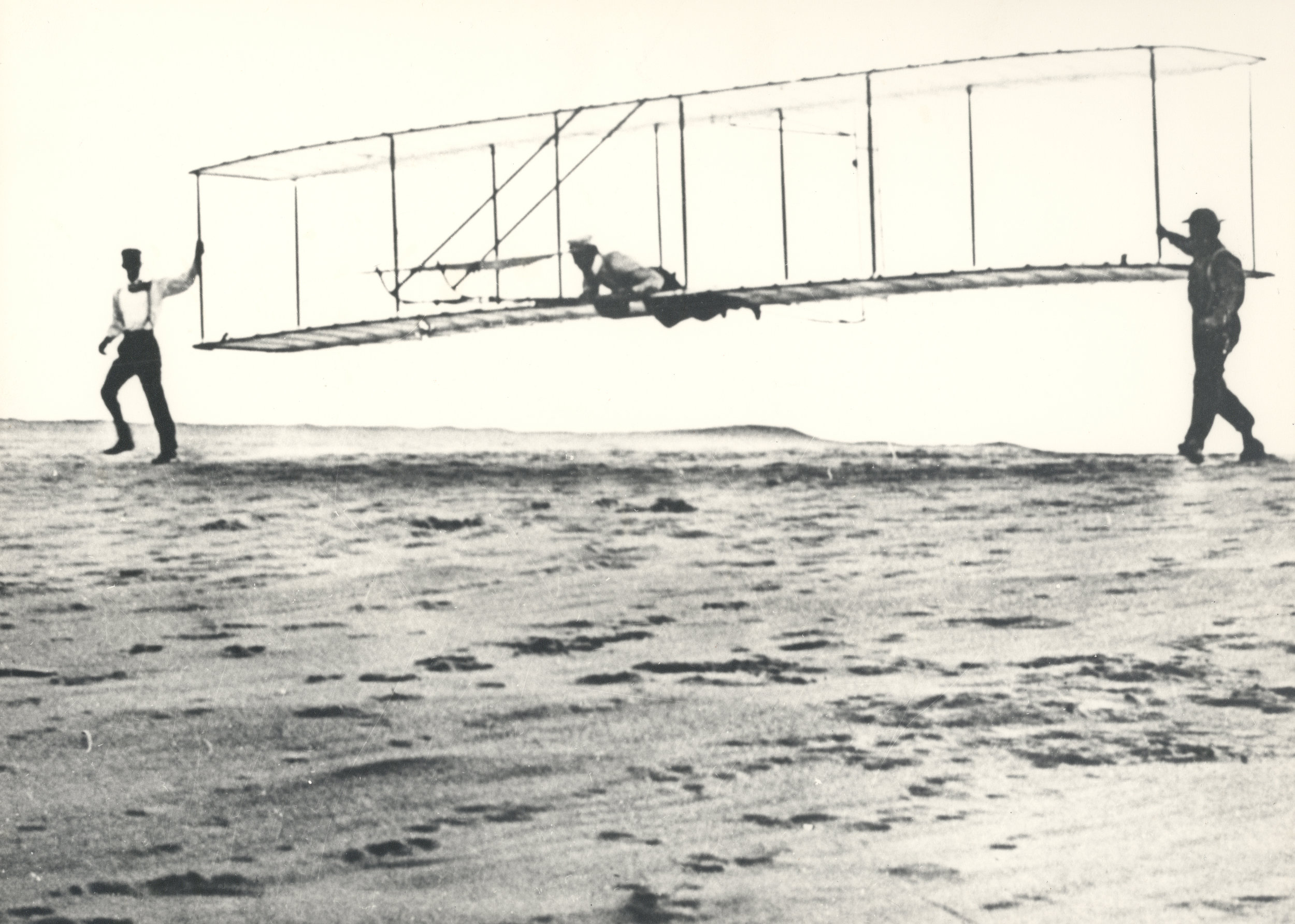

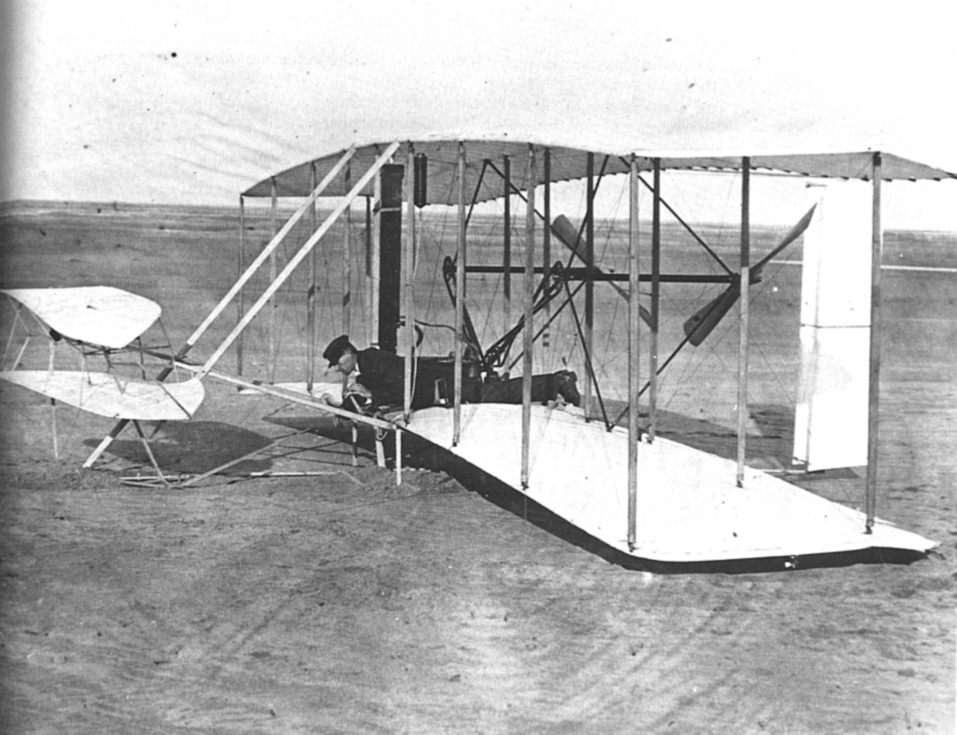

In his first letter, Wilbur had outlined their plans for flying while on their glider. But, as the brothers explain in a 1908 article in Century Magazine, once at Kitty Hawk in October 1900, they found that stronger wings would be needed to support both the glider and an operator. Not discouraged, the brothers were pleased to find that their design balanced beautifully in the air (see "The Wright Brothers' Aeroplane," referenced above).

The brothers' experiments at both Kitty Hawk and Kill Devil Hill, North Carolina, would last for years, each time following on the improvements made from the insights of the year before. To learn more about various iterations of the brothers' flying machines and their documentation in notebooks and through photographs, read Part II of The Wright Brothers: A Flying Idea.

Additional Resources

Orville Wright's will stated that his executors could determine which institutes should receive the Wrights' papers. The Library of Congress was allowed to select certain works. They chose 100 printed items, 303 glass plate negatives of photographs, the Wright-Chanute correspondence, and some family correspondence. For access to these documents, visit the Digital Archives site containing the Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers.

The remaining documents were shared amongst family members. Over the years, many of the documents were bestowed upon the Wright State University Library to serve as the permanent repository for those documents. To view photographs and additional primary sources, visit their Special Collections and Archives.

For more details regarding Wilbur and Orville Wright's process of inventing the Flying Machine, visit the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

For more information regarding the history of aviation, visit To Fly is Everything, a digital library put together via the efforts of Professor Gary Bradshaw at Mississippi State University and his team. The website includes transcripts of significant primary documents, short biographies of influential aviation inventors, and images. This "bird's eye view" of the history of aviation reflects the notion that ideas are built by standing on the shoulders of giants.

While there are many biographies of the Wright Brothers, David McCullough's book sparked my own personal interest in the Wright Brothers' efforts. The book provides a wealth of primary sources that served as starting points for more in-depth research at the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution Archives. A short video with McCullough (3:29) accompanies this article from Biography.

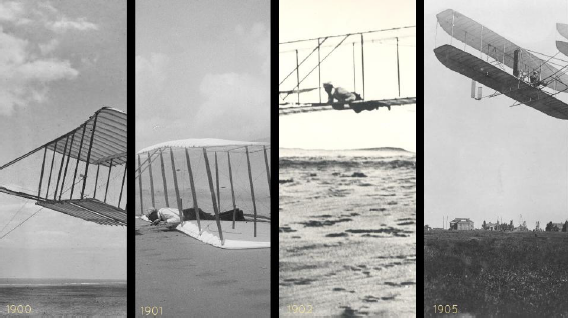

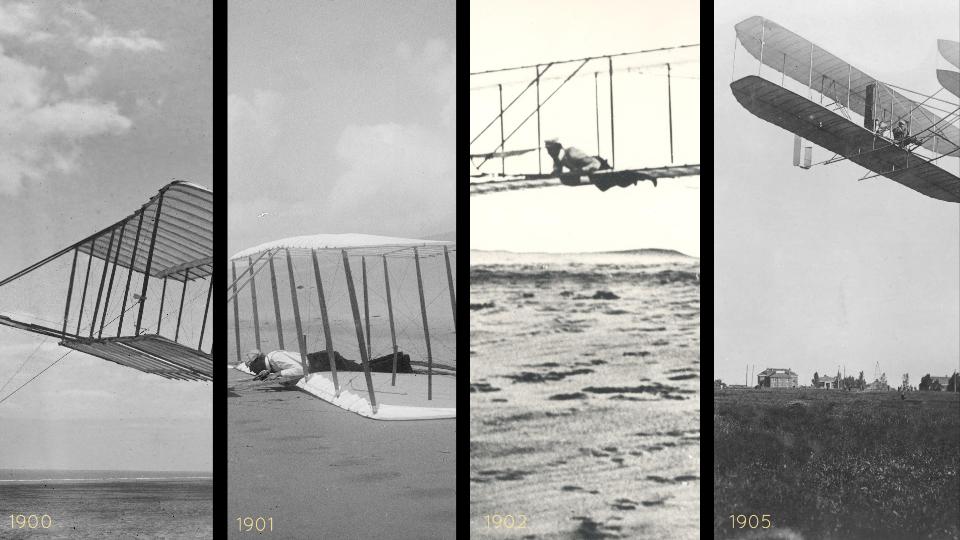

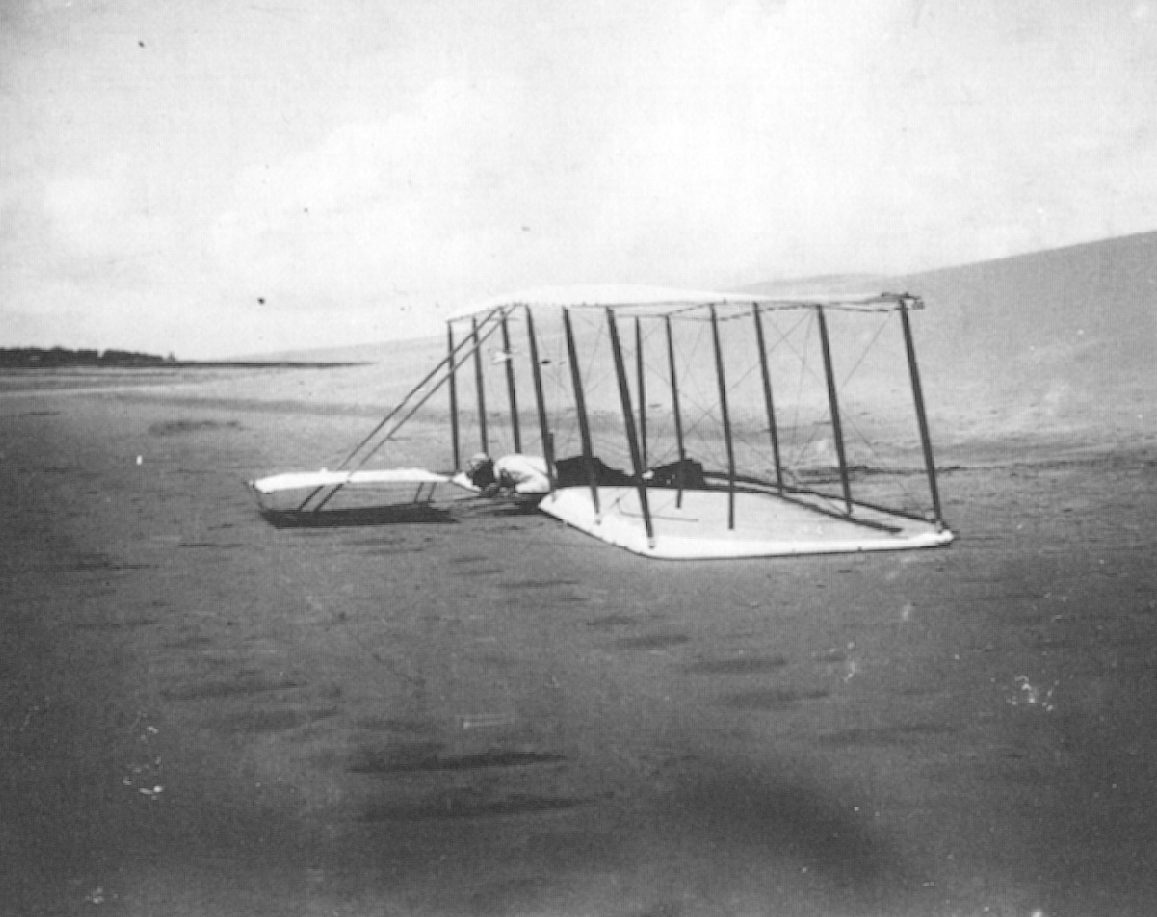

*Frontispiece

Collection of images from Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum