Henri Matisse: Drawing with Scissors, Part I

"Lateness is being at the end, fully conscious, full of memory, and also very (even preternaturally) aware of the present." —Edward Said, "Timeliness and Lateness," On Late Style

For Matisse, the new language of his papiers découpés, or "paper cut-outs," bridged a gap between drawing and painting. In his seventies, newly divorced after 41 years of marriage, exiled to the countryside by the ravages of World War II and recovering from a highly invasive surgery for colon cancer, Matisse found his "second life" (as told in a letter to his son) through the cut-outs. This cut-out method can be considered Matisse's late style.

In Part I of this two-part article, we look at the years leading up to Matisse's full embrace of the cut-outs as an art in themselves and not merely as a means for realizing large-scale projects. "Drawing with Scissors, Part I" looks at the context from which his late style emerges. His search for a medium that could lessen the distinction between drawing and painting, the impact of World War II and the state of his own health as he prepared for the very real possibility of death all played a role in the visual language he created for himself.

In Need of a New Language

"But a drawing by a colorist is not a painting. It needs to be given an equivalent in color. That is what I cannot seem to manage." —Henri Matisse, letter to Pierre Bonnard, January 13, 1940

Paper cut-outs provided Matisse with a renewed sense of spirit precisely because they resolved the gap between drawing and painting, line and color. In a letter to his friend Pierre Bonnard (January 13, 1940), Matisse shares the tension he felt between drawing and painting at this point in his life:

Your letter this morning finds me feeling depressed, deeply disheartened, and therefore quite unworthy of your praise, however much in harmony with my desires your words may be. For I find myself paralyzed by I don't know what convention that prevents me from expressing myself as I would like in painting. My drawing and my painting are separated.

The tension extends further to his desire for capturing spontaneity in contrast to the long periods of time that painting required in order for him to create the color compositions he sought. In the same letter to Bonnard, he continues:

My drawing suits me well, for it conveys what I distinctly feel. But my painting is bridled by the new conventions of flat color with which I must express myself completely, purely local colors lacking in shading and modeling, which must react with one another to suggest light, spiritual space. That hardly sits well with my spontaneity, which makes me balance a long period of work in an instant, because I reconceive a painting several times during its execution without really knowing where I'm going, relying on my instinct.

His process for painting had always been riddled with multiple sketches, repeated themes, and repainted portions of the canvas. But such a process required both a mental and physical stamina that was not so readily available to an ill and aging man.

There is a touch of renewed liveliness in the letter, though. He writes:

After much experimentation, I have arrived at a manner of drawing that has the spontaneity that gives full vent to what I feel, but that technique is exclusively my own, as artist and viewer.

Though he does not explicitly state the new method, the date of the letter aligns with the point at which Matisse begins to embrace his cut-out method as an artistic language in its own right.

Destruction and Creation: New Message, New Medium

Up until the late 1930s, Matisse had relied on the cut-out method as a tool for envisioning large-scale projects (see Part II for details). Matisse's physical and mental condition would call for a new means of expression. In January 1941, Matisse underwent surgery, which afterwards relegated him to a wheelchair while he recuperated. Spending long hours in bed, he would nonetheless summon the energy to paint. Gradually though, he began to turn to the cut-out method more frequently.

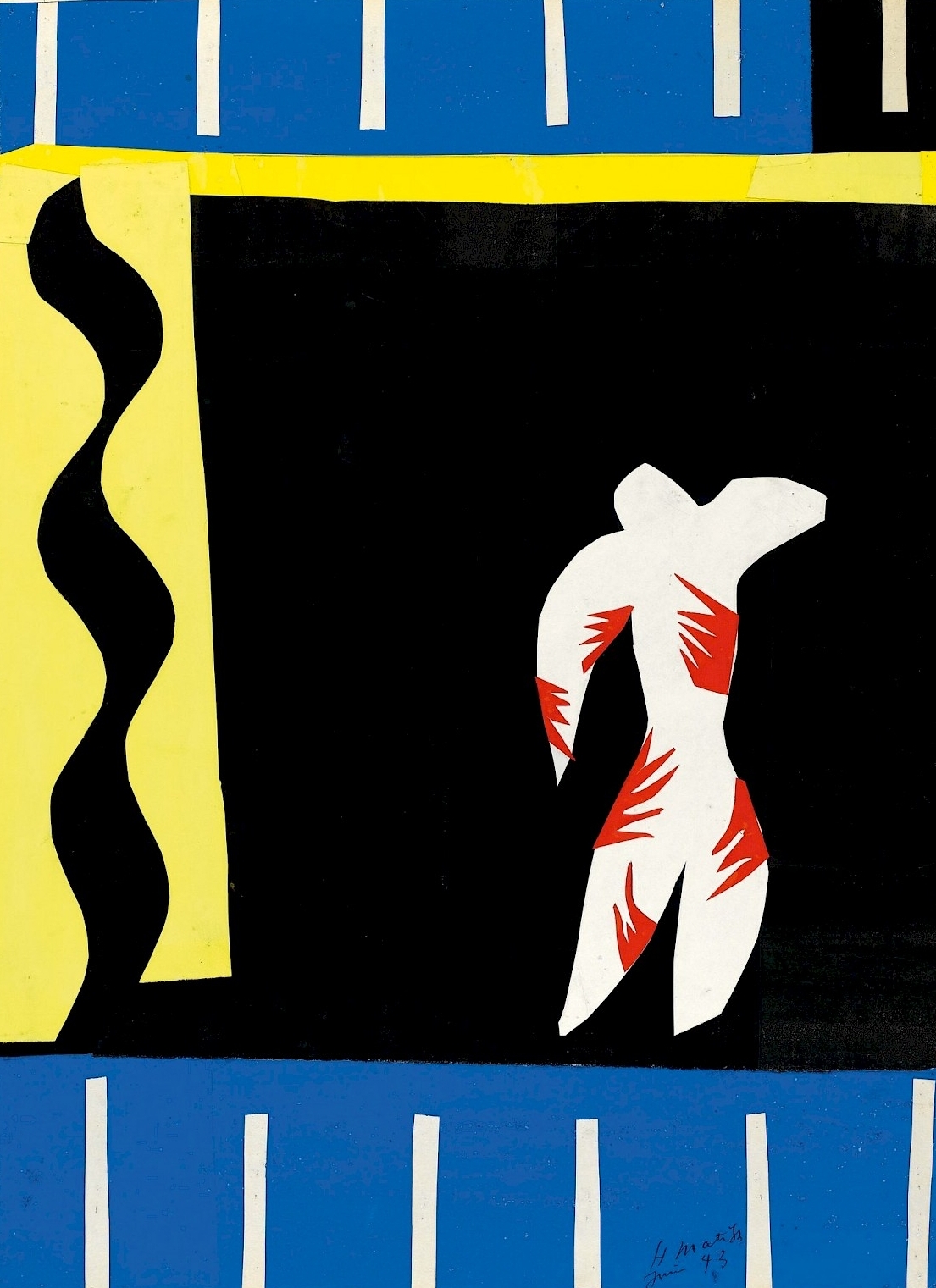

By 1943, Matisse began producing small cut-outs, pinning together the pieces onto cardboard that rested upon his lap. These cut-outs introduced a new subject to Matisse's compendium of themes. Of the Fall of Icarus, Matisse's personal biographer of sorts, Louis Aragon, wrote:

It was in the summer of 1943, the darkest point of that whole period, that he made an Icarus....The Fall of Icarus...between two bands of deepest blue, consists of a central shaft of black light with Icarus laid out against it in white like a corpse, and from, what Matisse said himself, it seems that the splashes of yellow—suns or stars if you want to be mythological—were exploding shells in 1943 [as quoted in Spurling].

Much of Matisse's work seems impervious to the ravages of war. In reading about this period of Matisse's life, however, one realizes just how much is kept out of the paintings. Even as a sick man, he was transported further and further south as German and Italian troops encroached; bombs could be heard falling all around, close enough to cause the front door to rattle; he was also well aware of the Jewish neighbors being captured.

More personal yet, in 1944 his daughter, Marguerite, had been captured and tortured nearly to death by the Gestapo upon discovery of her role in the French Resistance. She only barely escaped being sent to the Ravensbruck concentration camp. An air raid forced the train she was on to a halt just outside the border between France and Germany and she was later found hiding in the woods by local Resistance members. For months no one knew of what had caused her disappearance. Even Matisse's ex-wife served jail time after being arrested by the Gestapo for her work in the underground resistance movement.

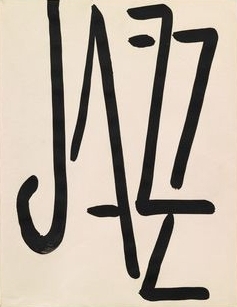

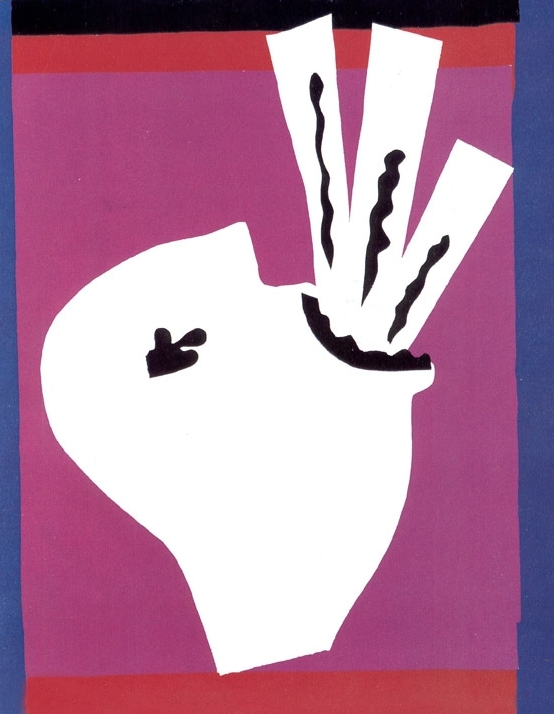

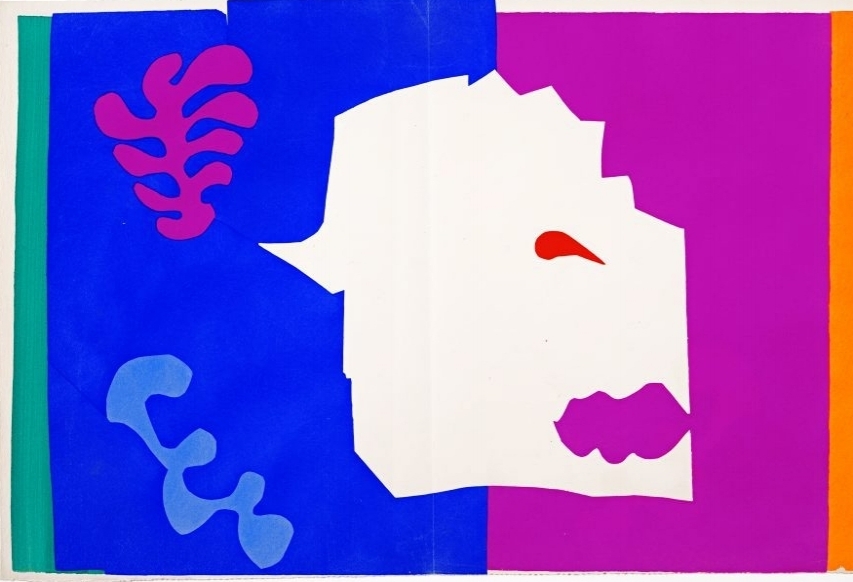

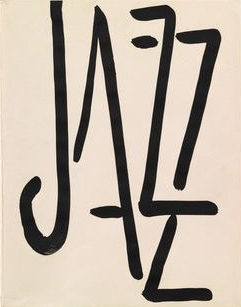

Below are images from Jazz, published in 1947, but which consists of some of Matisse's first cut-out images created in 1943 that stood on their own as "cut-out artworks." A total of twenty images were published, including an introduction by Matisse himself.

Metropolitan Museum Curator Rebecca Rabinow connects the circus-influenced images to the surrounding context of World War II:

Matisse's cut-out method would continue to expand into an even more robust form of expression for him in the following years. To read more about how the cut-outs morphed from a means for planning large-scale projects into its own mode of expression, look for the upcoming article, "Drawing with Scissors, Part II."

Additional Resources

The most comprehensive biography on Matisse is written by Hilary Spurling. Matisse the Master is the second volume in a two-part series and covers his most productive years as an artist, from 1909-1954.

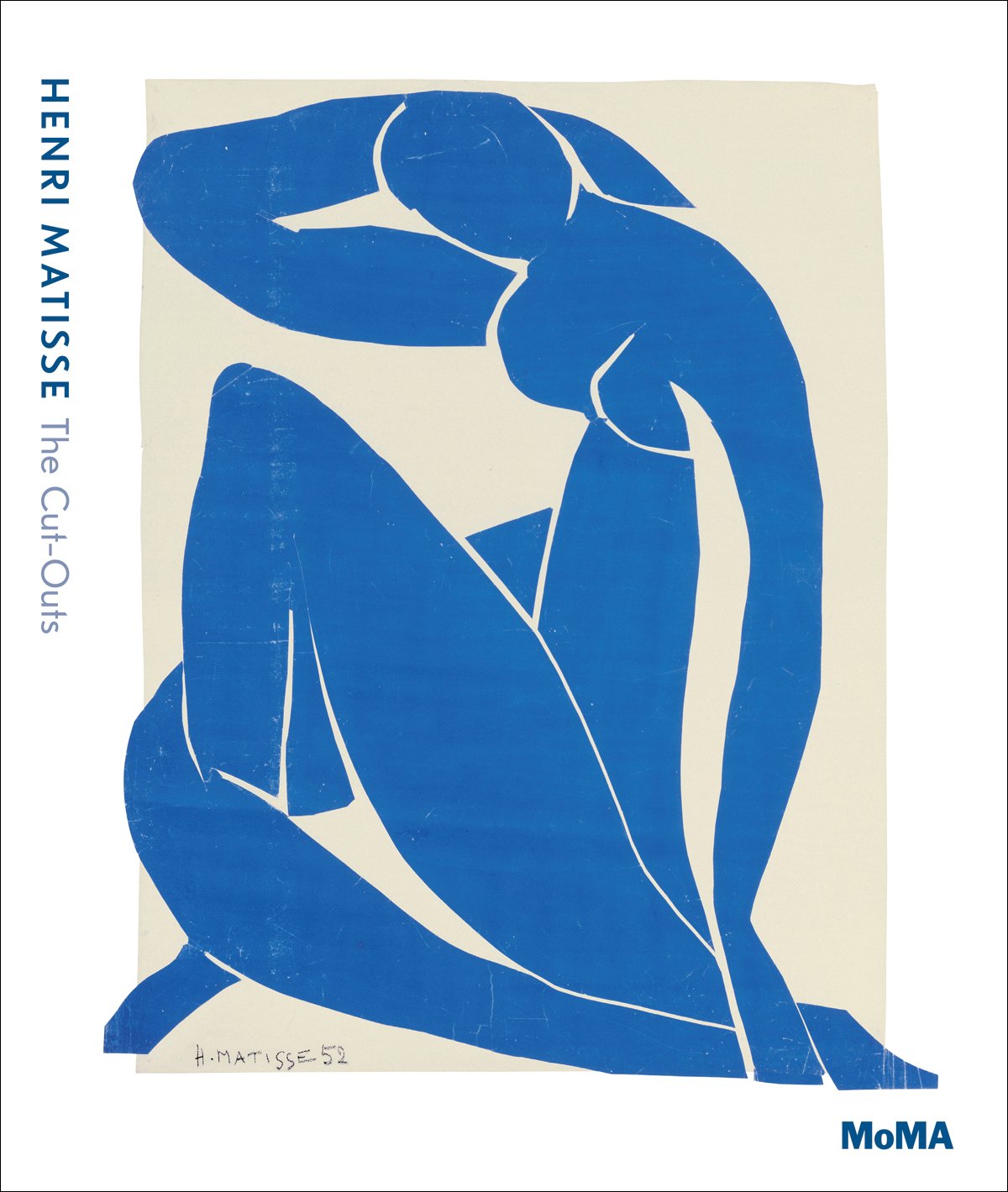

Henri Matisse: The Cuts-Outs is filled with essays on the evolution of this style. A preview of the book includes the essay "The Studio as Site and Subject" and also includes a number of images from the era.

Matisse:A Retrospective is a rich trove of primary sources, including letters and interviews by Matisse.

The introduction to Jazz is handwritten by Matisse and includes his description of his cut-outs as "drawing with scissors." A thumbnail collection ("Gallery Guide") of the images is available from the Des Moines Art Center.

All works by Henri Matisse © Succession Henri Matisse

*Frontispiece

Henri Matisse (1943), Icarus, gouache on paper, cut and pasted, 17 1/8 x 13 3/8 in. Centre Pompidou, Paris.© Succession Henri Matisse. Photograph by Iliana Gutierrez