Joan Miró: Threads of the World

"I provoke accidents, a form, a spot of color. Any accident is good." —Joan Miró, interview with Georges Charbonnier, 1951

Between Artist and Artwork

For an audience, the most visible aspects of the creative process tend to be that which can be identified most easily: the product and the person. Paintings can be studied and admired for their fulfilling sense of completion. Artists can be admired for being the source of such a distinguished product. Those artists whose personality and skill reach grand proportions may even be hailed as geniuses, as if their art were the mere result of muses and not of diligent work.

To catch sight of both the product and person in progress is to see a dimension that is usually kept from view. When we are only given access to the finished masterpiece or when we equate ideas with genius, we overlook the work it takes to nurture ideas into existence. One might even go so far as to say that we can be misled by the very completeness of a finished product, for it can suggest that there were never any obstacles—never any doubts—that stood between the artist's vision and the product. Without seeing what preceded the product, we have no way of knowing how it changed over time. By studying that in-between and kept-from-view dimension of creation, we add new layers for inspection.

Process: The Art of the Unseen

I work like a gardener or a wine grower. Everything takes time. My vocabulary of forms, for example, did not come to me all at once. It formulated itself almost in spite of me. Things follow their natural course. They grow, they ripen. You have to graft. You have to water, as you do for lettuce. Things ripen in my mind. —Joan Miró, Interview with Yves Taillandier (1952), "I Work Like a Gardener"

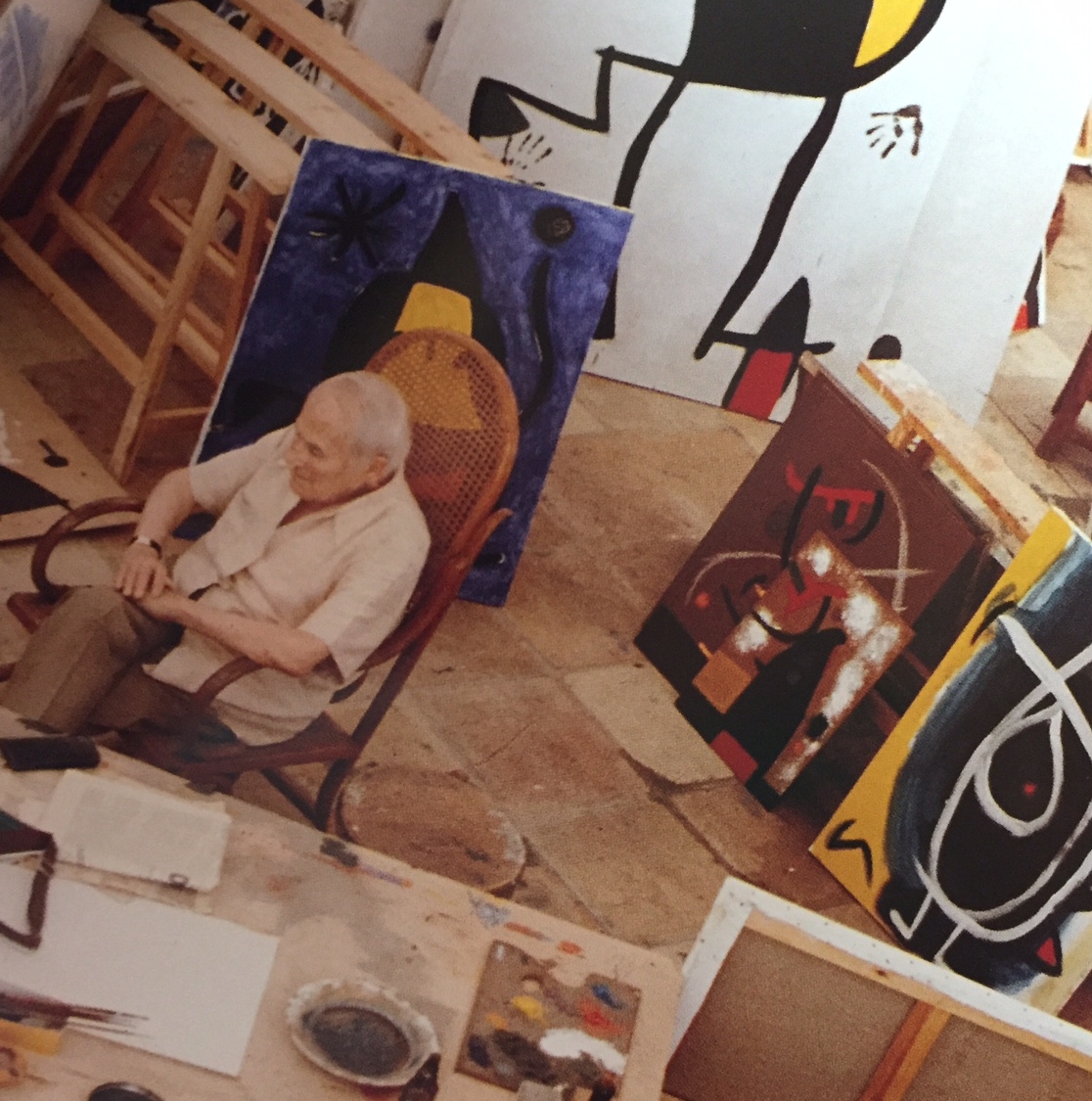

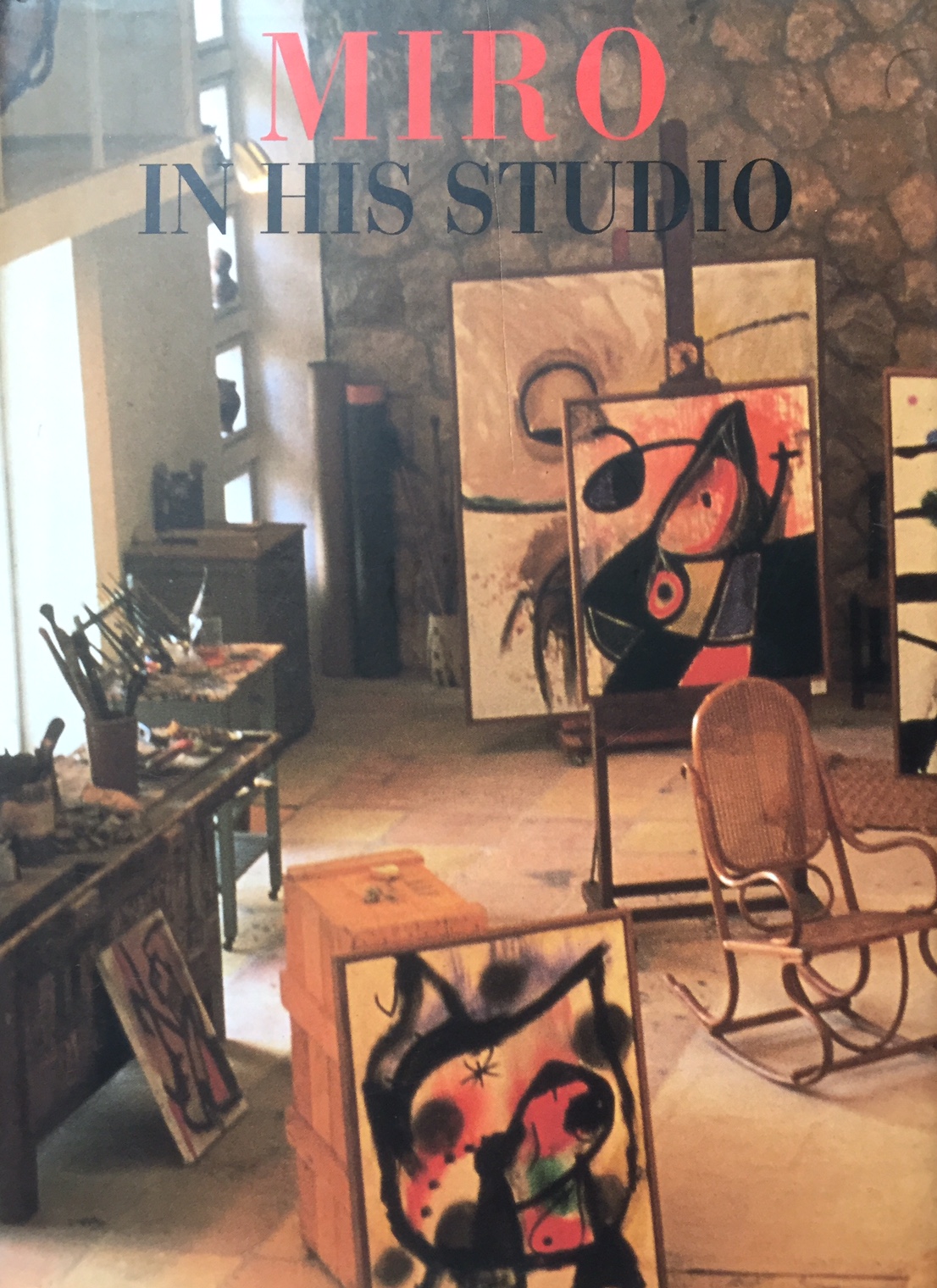

One such famous and prolific artist, Joan Miró, continues to be admired for the air of spontaneity and whimsy in his paintings. Miró understood, however, that spontaneity needed to be cultivated. Photographs by Jean-Marie del Moral, presented in collaboration with Miró's grandson Joan Punyet Miró in Miró: In his Studio, reveal the multifaceted approach to idea-building.

In his interview with Yves Taillandier, Miró expressed how even a "piece of thread can unleash the world." In The Captured Imagination, Miró scholar Margit Rowell elaborates upon the balance between rigorous practice and spontaneity:

Although methodical rigor was part of Miró's character and temperament, the state of innocence and amazement he sought to express would nonetheless be difficult to infinitely repeat, revitalize, and sustain. Miró continuously searched for catalysts to surprise and trigger his imagination.

The Poetic Shock of Objects

"I feel myself attracted by a magnetic force toward an object, and then I feel myself being drawn toward another object which is added to the first, and their combination creates a poetic shock." —Joan Miró, Letter to Pierre Matisse, 1936

His grandson, Joan Punyet Miró, shares that Miró could be found in his room of collected images, contemplating possible sources of inspiration. When an idea struck him, Miró would quickly capture the vision on any available surface. Punyet Miró writes:

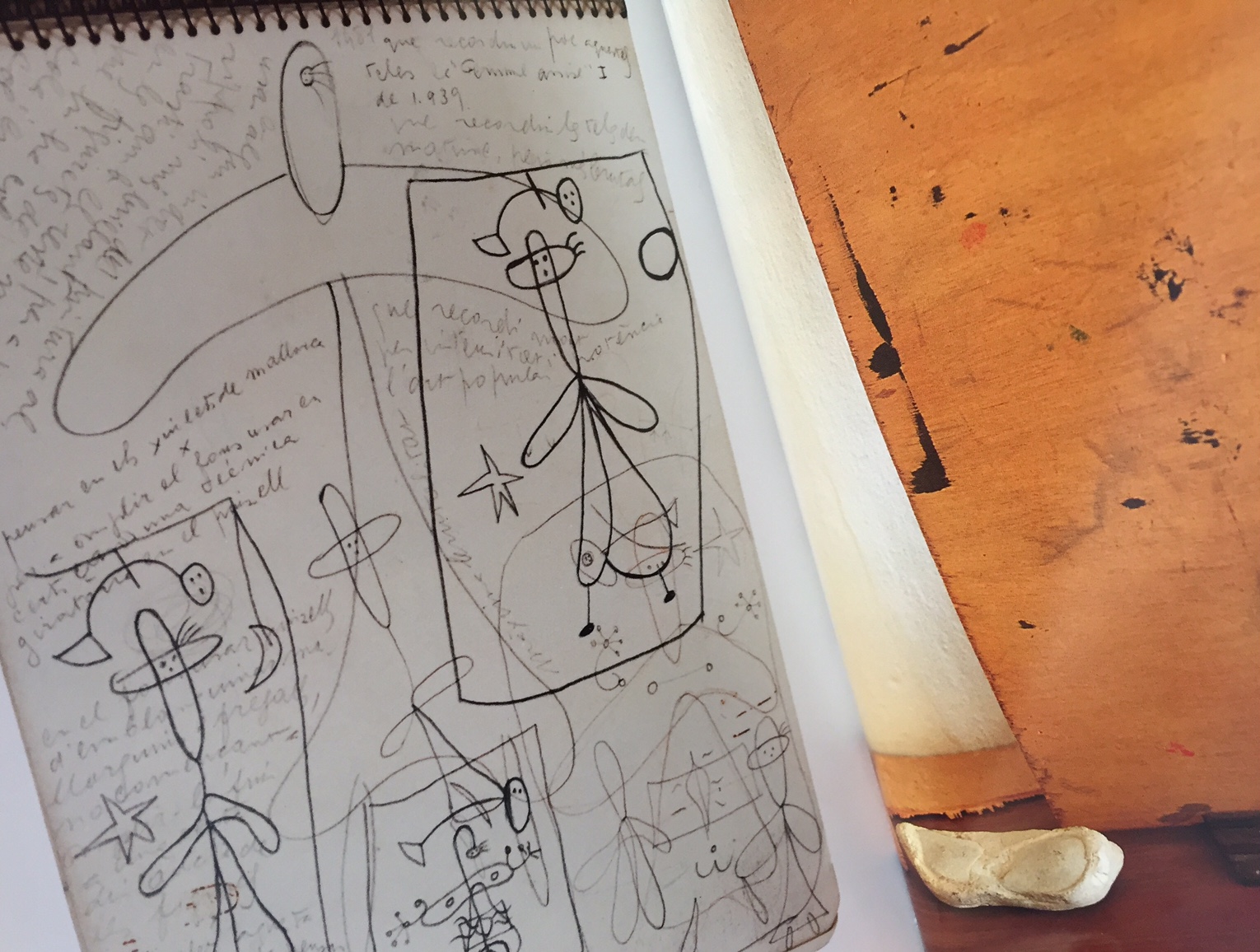

In the Sert studio there were innumerable preparatory sketches on all sorts of backgrounds: printed materials, newspapers, the backs of letters, butcher's wrapping paper, bus tickets...Ideas put down on the first piece of paper that came to hand, and then repeated much later as a point of departure.

Rowell elaborates further by adding that Miró's paintings were "frequently an enlargement and development" of the "visual ideas" that he captured on the scraps of paper. While the spark of an idea may indeed happen in an instant, it often takes much longer to work out the undefined edges of an idea. To accommodate the fluctuation of pace inherent in working with ideas for long periods of time, Miró kept multiple canvases in progress. He shares in an interview with James Johnson Sweeney:

For this reason I always work on several canvases at once. I start a canvas without a thought of what it may eventually become. I put it aside after the first fire has abated. I may not look at it again for months.

While Miró's goal may have been to present the sense of spontaneity, some of his works took years to complete. In an interview with Georges Raillard, Miró described the trouble he had been having with one of his paintings:

I began this painting two or three years ago and I realized that it did not really work. This preyed on my mind. Then it suddenly came to me that three strokes were missing. When I realized this I added the red at the side. Now it's good.

The visual presence of his unfinished ideas allowed Miró to ponder their completion.

Working Notes: Advice from Miró to Himself

From his notes and interviews, we can see how he devised methods for cultivating the intuitive spark. Below are some of his notes for "provoking accidents:"

"Use things found by divine chance: bits of metal, stone, etc...That is the only thing—this magic spark—that counts in art. I must have a point of departure, even if it is only a grain of dust or a flash of light."

“Melt down the metal of my empty paint tubes and use the resulting shapes as my starting point."

"Keep a blank sheet of paper for trying out pencils of different numbers and then take the little bits of lead you get from sharpening the pencils, crush them into the paper and start from there."

For Miró, to come up with new ideas was an active search for visual stimulation. Knowing this, he purposefully created opportunities to surprise himself. His methodical approach to spontaneity was an essential aspect of his creativity.

Additional Resources

The book Miro: In his Studio is a beautifully crafted glimpse into Miró's creative methods. With an introduction by his grandson, Joan Punyet Miró, and photographs by Jean-Marie del Moral, we are given unique access to how Miró worked. To read more about Miró's studio and to watch a video of his two Spanish studios, check out the Noble Oceans article, Joan Miró: Studio as Home.

To view preliminary sketches and a short video of the 1925 painting, The Birth of the World, visit the Fundació Joan Miró. Compare the sketches to the original painting (and listen to curator Anne Umland's notes on the painting) by visiting MoMALearning.

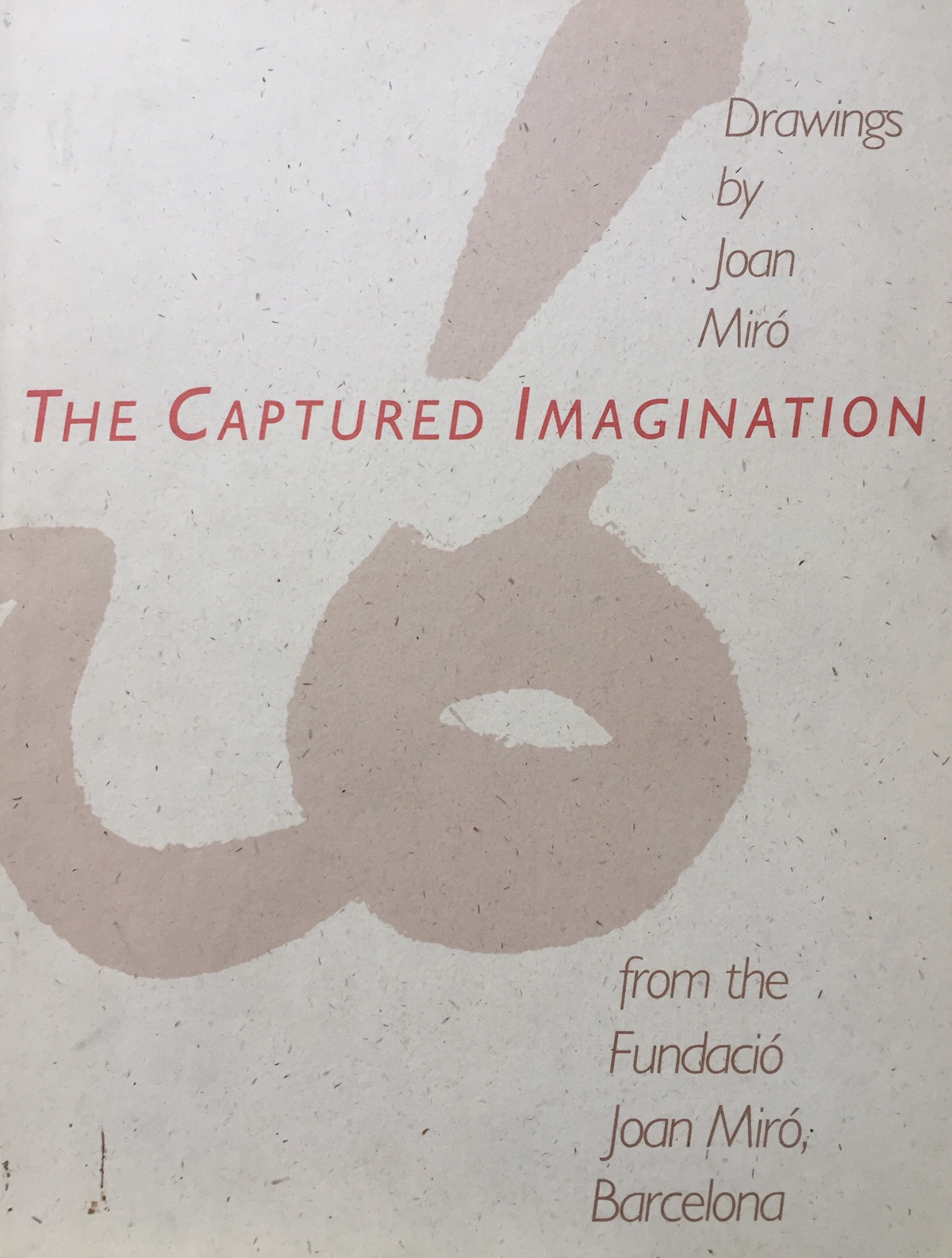

In The Captured Imagination: Drawings by Joan Miró from the Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, art historian Margit Rowell collects preparatory sketches that span Miró's full career (including sketches from childhood!). Her introduction covers various creative techniques expounded upon by Miró in letters and interviews—from how he chose which sketches to develop further, to how working with diverse mediums (sculpture, ceramics, textiles) helped to keep ideas flowing. Margit Rowell's Selected Writings and Interviews is a gem for anyone interested in reading more about how Miró approached his work and how he thought about art in general terms, as well.

*Frontispiece

Miró, Joan (1925). Preliminary sketch of the work "The birth of the world." Fundació Joan Miro. © Successió Miró, 2016